The Benelli Museum honors a world-class motorcycle company and the six brothers who started it all

As a young boy growing up in the shadow of the Motobi factory in Pesaro, Italy, Paolo Marchinelli regularly watched the motorcycles being packed onto trucks and sent around the world. He says it was easy to fall in love with the lightweight bikes that won over a thousand races in 20 years.

In the town nestled on the Adriatic coast, Marchinelli’s passion for Motobi was a communal sentiment. He remembers getting his first Motobi, a red 1967 Mini Bike, and finally being able join the rest of the boys in his neighborhood.

“In Pesaro there were packs of young boys with these bikes,” Marchinelli says as he’s thumbing through a photo index of Benelli and Motobi motorcycles, looking for the bike he used to own. “When I got this moped I had the same feeling as all of the other boys.”

Wearing a bright red vest over a light blue polo, his slicked-back white hair nearly reaching his upturned collar, Marchinelli flips through a few more pages in the catalogue until he lands on a red 1969 125 Sport Special, the first proper motorcycle he acquired when he was 16.

“This was a very fun bike because of the roads we have here in Italy: very curvy, up-and-down roads,” he says, staring at the image of Sport Special. “It was a very dangerous game, but it was a very fun game. Many times we would meet up with these bikes for real races.”

Now nearly 50 years removed from the perilous races of his adolescence, Marchinelli leans back in a brown tufted leather sofa situated in the entrance of the Benelli museum. Marchinelli is the secretary of two associations that opened the Benelli Museum two years ago: Moto Club Tonino Benelli di Pesaro and Registro Storico Benelli (the Benelli historical club). A wall of trophies, plaques, and engines sprawls behind him. In front of him are murals of Benelli’s most decorated racers and a couple of the bikes that gave the company, known by its signature logo of three stars and a lion, worldwide recognition.

It’s a warm June evening, moments before the museum is about to close its doors for the day and there are no visitors left. Marchinelli remembers how the Benelli and Motobi factories, both of which located in Pesaro before consolidating into one company in 1962, were sources of fame and richness for the city. Not only did the local factories employ many Pesaro residents, they also made the city a household name for motorcycle enthusiasts around the world.

Pesaro’s stature as a motorcycle-manufacturing hub through the early 20th century was a result of the determination and craftsmanship of six brothers by the name of Benelli. From his spot on the couch, Marchinelli points to a black and white mural of the brothers atop the trophy case. From oldest to youngest, Marchinelli describes the distinct role each brother played to shape Benelli into the world-renowned brand it has become in the last 106 years.

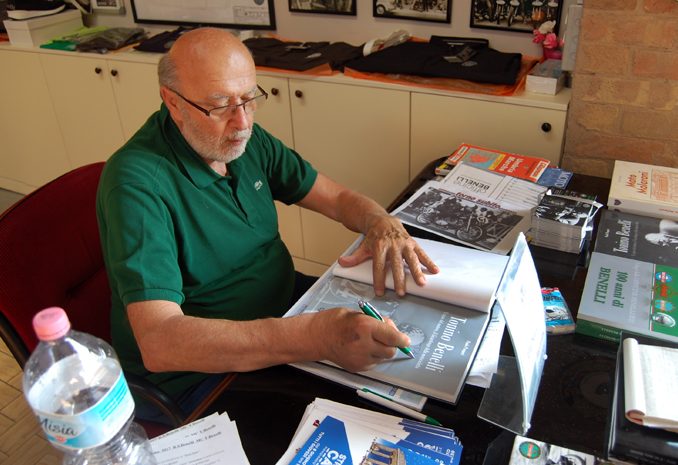

Black and white photos of the historic Benelli factories and books recounting the company’s history are scattered throughout the museum. But perhaps the greatest source of information on the origin of Benelli is a colleague of Marchinelli’s, Paolo Prosperi. He didn’t grow up riding Benellis, but the vast history behind the motorcycles made him as passionate about the brand as anyone else who has set foot in the museum.

Prosperi, the president of the Benelli historical club for owners of classic Benellis, uses a cane to help him maneuver through dozens of rows of motorcycles that fill the rooms of the Benelli museum. He still rides a vintage cherry red Motobi moped around Pesaro and he can recount the history of Benelli as if he were the seventh brother.

On a sunny Tuesday afternoon, Prosperi, wearing an untucked green polo shirt and red-rimmed glasses, fills the museum entryway with his bellowing voice before he even steps into the room. Immediately he is illustrating how a small mechanical garage operated by the Benelli brothers transitioned into making world-class motorcycles. He explains that before World War I it was difficult to find the pieces needed to repair cars and other machinery. Thus, the Benelli garage became famous for its ability to make quality parts for automobiles, motorcycles, and rifles. However, like many other Italian factories at the time, the government directed the factory’s efforts to creating equipment needed for the war.

From oldest to youngest, Marchinelli describes the distinct role each brother played to shape Benelli into the world-renowned brand it has become in the last 106 years.

Following the war, the garage could focus on the needs of civilians, “By this time the garage had become so famous that FIAT, Alfa Romero, and many other brands had given the Benellis the opportunity to work for them,” Prosperi says.

Prosperi goes on to say that the number of civilian motorcycles in Italy had dropped from 19,000 to 4,000 bikes following the war. Instead of taking jobs with some of the biggest brands in Italy, the Benelli brothers, led by Giuseppe, turned their attention from the mechanical garage to fulfilling the need for civilian motorcycles under the Benelli brand.

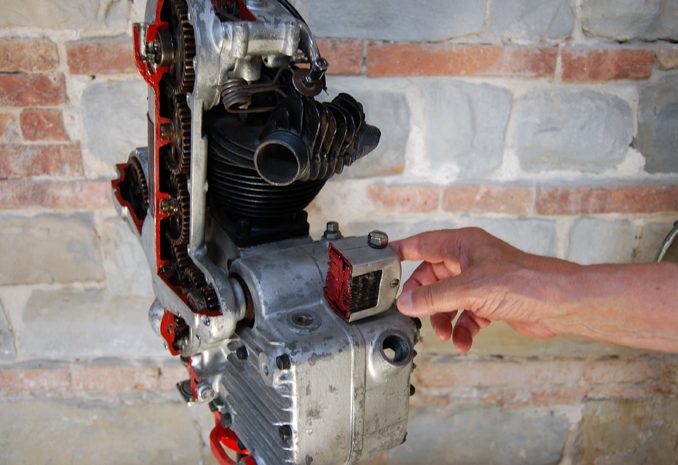

Standing in front of the decorated trophy case, his voice echoing through the museum, Prosperi describes the first engine produced by Benelli: a 75CC two-stroke auxiliary engine applied to bicycles.

He says this initial engine failed because of damage caused by its vibration, but the failure led to the idea of creating lightweight motorcycles. In 1921 the company presented the “Velemotore” motorcycle at a Milan motorcycle show, officially introducing the Benelli brand to the motorcycle market.

Prosperi taps the tile floor beneath the historic bikes he’s describing, his passion for the motorcycles on display as much as the mounted motorcycles he is describing.

“Do you see the chain?” exclaims Prosperi, slapping his cane on the white fence in front of the motorcycles to point out the transmission on a classic Benelli. “Benelli motorcycles always use a chain transmission—never a belt.”

Next Prosperi points to a rusted out vintage Benelli sitting in a far corner of the museum. It is stationed in a model workshop, complete with old tools, vintage oil signage, and two mannequins working on the bike. Under the bike, is an inscription with the year 1927 and the name of motorcycle’s original pilot, perhaps Benelli’s most prolific racer: Tonino Benelli.

Tonino, the youngest of the six Benelli brothers, was the most successful racer of the family. His image can be found throughout the museum in murals and photos and on a bronze bust. Tonino is synonymous with Benelli and the museum, and no one bears more information about the world-class racer from Pesaro than Prosperi, his biographer.

As if reading from the book he wrote—copies of which are stacked at the reception desk of the museum—Prosperi describes Tonino’s racing career from his first race in 1924, up until his fatal crash in 1937, and the four Italian championships in between.

“In 1924 he starts to race and he has his first victory,” Prosperi explains. “He went to Bergamo San Vigilio: It was a hill climb and his first victory in only his second race!”

Tonino’s death in 1937 was a significant blow to Benelli, but nothing like the introduction of Japanese bikes into the motorcycle market in the late ’60s, or Alejandro De Tomaso’s subsequent purchase of Benelli in 1971. In Prosperi’s opinion, Tomaso’s purchase of the classic motorcycle brand was a result of a large management team made up of many Benelli descendants that each wanted to take the company in a different direction. Prosperi stresses that Tomaso’s purchase of Benelli was a business decision, rather than one guided by love for the brand.

In front of motorcycles from the 18-year Tomaso era, many of which are models copied from Honda and Yamaha motorcycles made in the same time frame, Prosperi makes it clear that Tomaso was the least passionate owner of the company. But he says neither of the preceding owners, Giancarlo Selci or the Meloni group, were able to capture the elusive spirit inherent to the original Benelli bikes.

Despite the various ownership regimes and unoriginal models Benelli has produced since the late ’70s and ’80s, tourists, or Pesaro residents can still feel the intrinsic soul of Benelli bikes by taking vintage Benelli tours hosted by Moto Club Tonino Benelli di Pesaro.

According to Marco Vanzolini, the Moto Club tour manager, the club hosts multiple tours every year ranging from weekend trips to week-long excursions. In the past, tours have gone as far north as Scandinavia and as far south as Sicily.

The tours generally average about 30 riders, but according to tour regular Mario Penserini, even in such large groups, it’s a pleasure to ride with so many people who share the same passion for Benelli bikes.

The type of bikes riders use on the tours depends on the specific tour. Most tours utilize classic bikes from the ’30s, ’60s and ’70s, but some use the more recent Benelli models, although they are less common. Regardless of the bike’s era, organizers say the rich history of the Pesaro brand commands respect from motorcycle enthusiasts around the world.

“In Sicily all the bikers from a different group couldn’t wait to show us around when they saw we were from Benelli,” Vanzolini says. “And the same thing happened in Northern Europe.”

In 2005 the Chinese motorcycle production company Qianjing acquired Benelli. There is still a Benelli facility just outside of Pesaro, but Marchinelli believes that most of the production comes from China. Despite their new birthplace, even the new Benellis can ignite that love for bikes in the kid from Pesaro.

“Even if they’re not pure-blood because they’re produced in Asia, they have that logo with the three stars and the lion, which makes you fall in love,” explains Marchinelli. “They’re still Benellis.”

Slideshow

This article also appears in Urbino Now magazine’s Sport section. You can read all the magazine articles in print by ordering a copy from MagCloud.