World War II Freedom Fighter who resisted Nazi German Occupation from behind the Gothic Line.

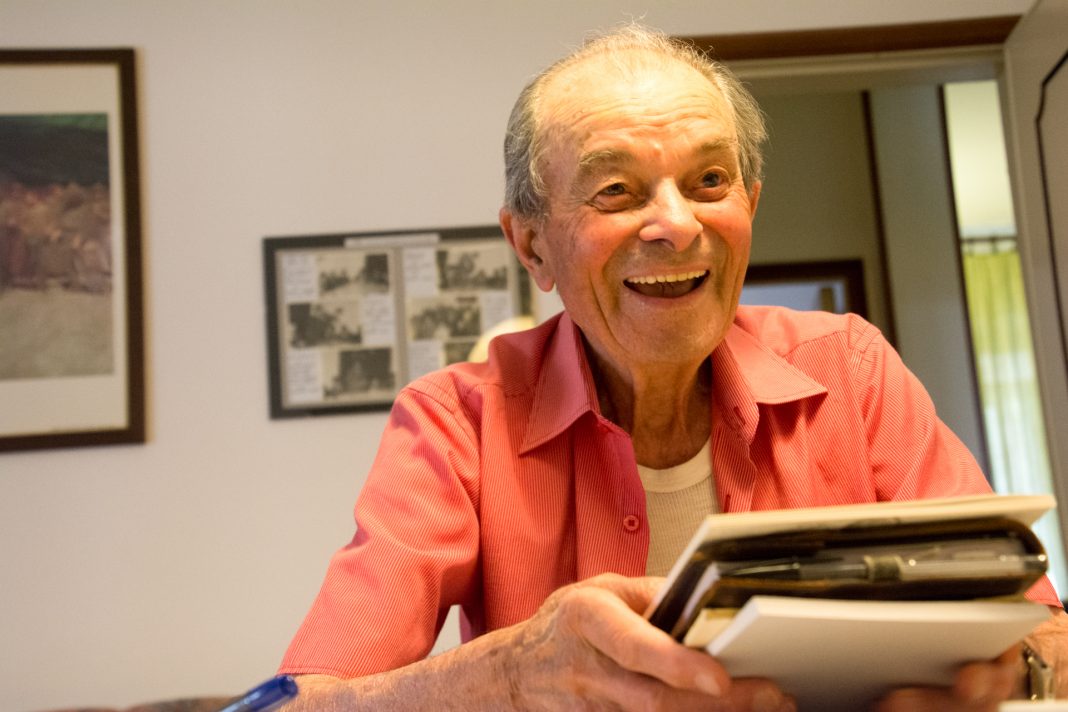

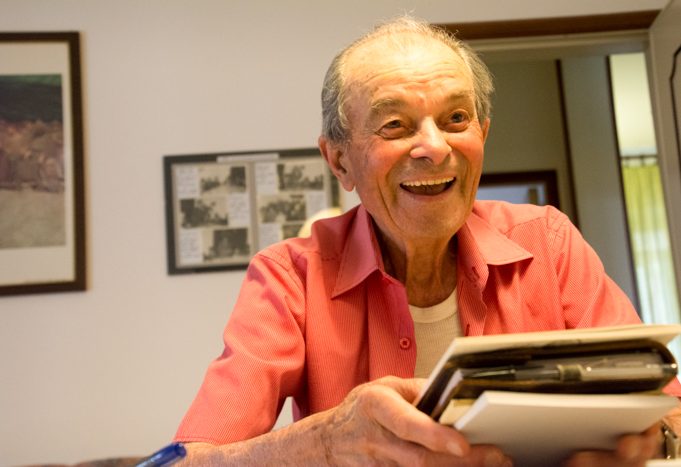

Umberto Palmetti, 92, has spent most of his life as a farmer. Palmetti lives in a one-bedroom home surrounded by books, pictures, and model tractors that he has meticulously constructed and bolted to his kitchen table.

He is one of the last remaining Partigiani, anti-fascist Italian Partisans who opposed Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and the German occupiers during World War II.

“I know about it because I lived it,” Palmetti said. “I was a Partisan.”

He grew up in the town of San Giovanni in Marignano, Italy, about 10 kilometers from where he lives now in Gabbice Monte.

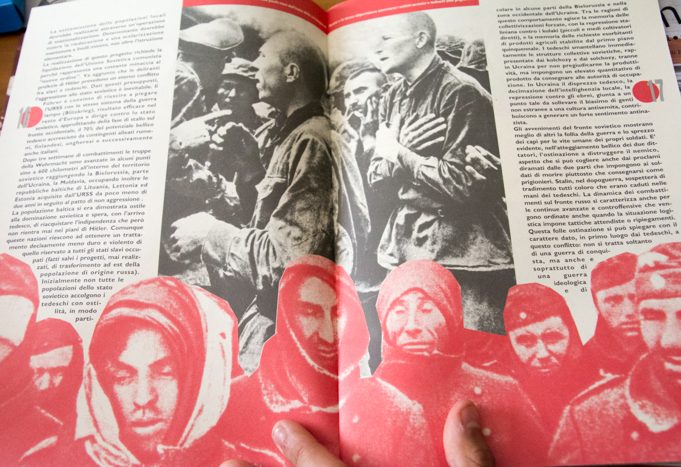

During the war, Italian civilians were forced to construct defenses as part of the Gothic Line to fend off the allied advance from the south.

“Many people sent to work were killed, and if you didn’t you would have been shot,” he said.

It would be silly to say ‘no I wasn’t scared.’

After escaping on foot from the Gothic Line construction in 1943, Palmetti recalls being put on a list of people to be shot by the Germans because he was a member of Italian Partisans.

“I have a document that [indicates] I was meant to be shot,” said Palmetti, as he holds out a piece of paper, enclosed in plastic, with the words: La Pena di Morte, or death penalty.

“It would be silly to say ‘no I wasn’t scared.’”

The Gothic Line was not an actual wall, but a series of strategic defensive points that took advantage of natural high points in the hilly terrain. It followed the Foglia river around its natural bends, and the Nazis destroyed many of the bridges across this river to prevent the advance of allied troops.

Palmetto said he was one of the Partisans who didn’t carry a gun.

“There can be heroic actions without arms.”

Partigiani played a crucial role in the dismantling of this last line of defense. The transfer of information — such as the locations of Nazi gun and explosive storages — was more important than trying to kill the German occupiers. Partisans primarily used guerilla tactics to disrupt the German war effort.

“My group did arrange the blast in Montecchio, Italy, on January 1, 1944, which detonated a Nazi explosive storage and destroyed the entire town,” he said. “Thirty kilometers away the windows of my house broke.”

The Germans used the castle in Tavoleto, a town located behind the Gothic Line, as a last defense location. Having almost a year to fortify the town, the Germans built pillbox bunkers, rectangular concrete boxes about 20 feet long, in the rolling hills. They also laid mines in many of the farm fields across the region.

Signorotti Luigi, a resident of Tavoleto and a local historian, was nine during the Battle of Tavoleto.

“Two German soldiers were found two days after the battle hiding in a mattress made of chicken feathers,” said Luigi. “The civilians returned them to the English.”

The Allies suffered 40,000 casualties during the Gothic Line offensive. Many of these were British soldiers and British Indian units known as the Gurkha.

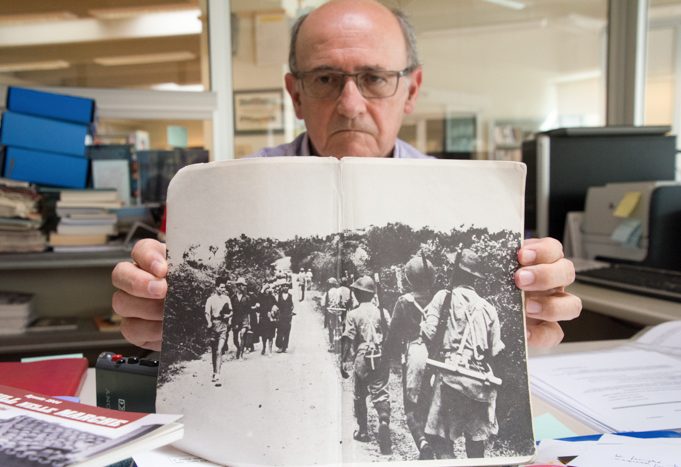

“Partisans made an alliance with the Italians who were forced to build this, so the partisans built it as slowly as possible,” said historian Mauro Annoni, president of the Institute of Contemporary History for the Province of Pesaro and Urbino.

Partisan action was resented by the Germans, and it resulted in more casualties for the Italians than for the Germans.

In April 1944, the Germans discovered that some Italians were siding with the Partisans and went to Fragheto, a town in the mountains of Italy along the Gothic Line. Here they massacred 30 of the 62 people living in the town.

“The town resented the Partisans after they had only killed one or two of the Nazi’s and the Germans killed half the town,” said Annoni.

Palmetti escaped on foot from the Gothic Line defenses where he was forced to work. According to Palmetti, it was difficult for the Germans to distinguish him from the other 17,000 workers.

“I knew that people were looking for me. I went home to change, and they were waiting for me, so I used the backdoor and managed to hide another day.”

For Palmetti, joining the Partisans was a political choice.

“We were people like everybody else, going with one side or the other. People my age didn’t have much of a choice. Either enroll in the fascist republic or hide.”

To share his memories of those days, Palmetti has written more than 1,100 poems about the war. Some of his work is published in his book “La II Guerra Mondiale: Pesaro-Rimini.”

The first stanza of “Fighters on the Gothic Line” by Umberto Palmetti reads:

We were together

In the scream of war

Overwhelmed by hate

Of meaningless talents

“I never fell into pessimism with this poem. It’s about war, but it’s also about nature, that we will come back after the war,” he said. “I always put in a bit of positivity otherwise I don’t like it.”