The Molaroni family has been part of the Italian majolica tradition for generations

Walking into Ceramiche Artistiche Molaroni, the Molaroni Artistic Ceramics store in Pesaro, you can’t help but hold your breath. It feels as if even a small breeze would break the intricate vases, plates, bowls, and clocks on display. Each item stands out as its own masterpiece. Tiny elephants and owls are covered in complex floral and vine patterns that almost look like real daisies and roses wrapped precisely around the pure white backgrounds. A large three-foot vase at the entrance stands out with powerful blues, yellows, and reds that catch your eye right as you walk in the room. Large and proud columns stand in the corners of the shop showcasing their clear and precise brush strokes. And in the back sits the creator of these timeless pieces, Marcella Jannone Molaroni. With hands laced together in front of her, she sits admiring the work of not only herself, but also her family who began the business almost 140 years ago.

The Molaroni family has been in the ceramics business since 1880, when Vincenzo Molaroni decided to open shop in Pesaro. Not only was Vincenzo a successful business man but he was also an artist. He created intricate designs on pieces of cooked pottery inspired by Raphael, one of the most influential Italian painters during the Renaissance. The motifs created by Raphael are represented in a Molaroni design named Istoriato, or Storied. The Storied designs are often depictions of biblical tales or early Italian myths. This specific design is one of 12 created by the Molaroni workshop and is one of the more complex.

The pottery created in the small workshop behind the storefront is called majolica, which means Italian glazed pottery. This type of pottery is dipped in a fast-drying glaze and is then cooked at extreme temperatures. This step is what makes majolica unique from other types of pottery. The glaze is tin-based and gives the ceramic pieces the signature pure white majolica color.

Today Marcella Molaroni is carrying on the family traditions as well as adding her own mark to the family business.

“In our family almost everyone paints,” she says, while sitting at the wrapping station, her hands folded over the custom designed wrapping paper she uses to protect the items bought in the store. “It was my grandfather’s life and the rest of his family have done the same thing for generations.”

Molaroni has been working in the shop more than 50 years and has created hundreds of pieces from the original designs made by the workers in her great-grandfather’s employ.

“As a Molaroni shop and family we follow tradition,” says Marcella Molaroni. “The people who come here know that here you can find classic pottery.”

The Molaroni family is unique in the ever-changing styles and motifs they create. Some of the 12 designs created in the workshop are historical, including the Storied designs based on Raphael’s pieces, as well as a more complicated style called Grotesque. Some designs are more art nouveau, which was the most avant-garde style at the time the businesses started, and some are based on ancient paintings but created by Molaroni herself.

Molaroni explains that the family’s influence has extended past the borders of Italy. She says that shipments are being made everywhere in the world and the company’s pieces are even seen in museums in Milan, New York, and Vienna.

In Pesaro the Musei Civici (city museum) carries multiple pieces from the Molaroni collection. Francesca Banini from the Department of Beauty in Pesaro was the original curator for the museum’s exhibit several years ago that featured Molaroni ceramic. “One artist stands out from the rest,” Banini says. “Ferruccio Mengaroni was an apprentice under the Molaroni family in the early days. He elaborated the styles of the 1400s and the 1500s and reinvented the Pesaro style of ceramics.” Mengaroni’s Medusa is displayed at the front of the Musei Civici to showcase the intricate designs created in the Molaroni shop.

“The process to make these patterns is more than hard to create,” says Molaroni, showing some of the ancient vases and plates in the Grotesque and Storied designs. The Grotesque motifs have large cherubs that fill in as handles for the vase itself. They have dark yellow wings that are detailed with intricate feathers and shading. Some of the Storied pieces are from the 1930s, she says. The motifs are based on real works of classical artists and in order to execute them to perfection a skilled hand is needed. “It takes a very long time—sometimes it takes up to a month—to create.”

The more modern designs are unique to each artist. They tend to be a combination of multiple different motifs allowing for more creative license for each artist. The design that offers the most artistic license is the polychromatic design, a kaleidoscope of different colors and images from all the designs offered at the Molaroni shop. Others such as the Rosa and Margherita designs were so popular in Pesaro that the city adopted the designed flowers as their own, dubbing them the Pesaro Rose and the Pesaro Daisy.

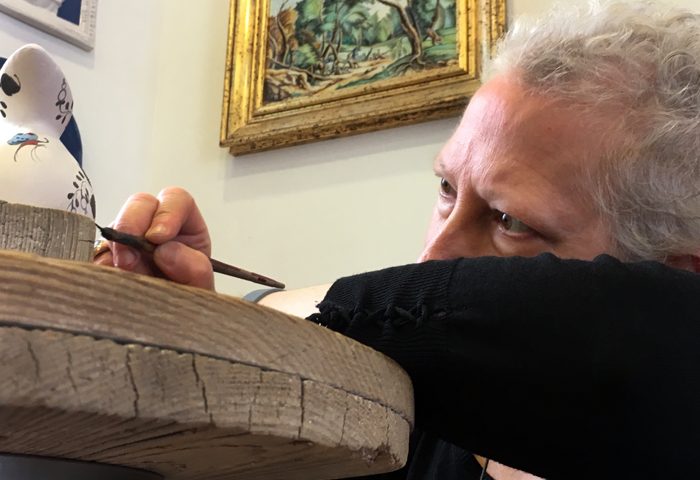

Molaroni’s hands seem to be made for painting pottery. As she slowly paints a rose on to a small white pitcher or draws long dark vines with the tip of a long red-handled paint brush, her movements are precise and calculated. It seems as if this process has been one that she has refined for the half-century she has been working in the small workshop.

“You just need experience and little bit of ability,” Molaroni explains, as she fixes a slight imperfection on the white paint of a tiny ceramic dove. “I have been doing this since I was six and now I am 59. Instead of going to kindergarten I was here, and back then there were a lot more people, around 35. I didn’t go out to play. I just came here after school: one hour in the shop and one hour in the back.”

The dove has a small chip in the white glaze right at the tip of the beak. Molaroni takes a small knife and begins to scrape away at the layers of white glaze. The ashes cloud around her, catching the light beams from the tall windows in the workshop, then stick to her black shirt. She picks up a paint brush, dips it in a blue bowl of white paint, and quickly dabs it on the cracked beak. In three seconds the whole process is over and the white dove is ready to be fired once more.

Molaroni learned among adult artists as a small child, watching how they made the different shapes from the stamps created by the workers who began the business in 1880. These “mother stamps,” as Molaroni calls them, are molds that were based on the ancient vases made by Raphael.

“The workers made all of the molds by looking at and drawing from the creations of Raphael,” says Molaroni, standing among the selves that hold every mold used in the shop.

In the back practically everything is covered with clay. The tools are layered with thin coatings that turn everything a light brown. The molds themselves are surprisingly clean. Each one is labeled with a large black number.

Molaroni carefully takes down one of the larger molds and sets it on the earth-covered table. It is surrounded by a thick rubber band that holds the pieces together. “The molds are sectioned out so that it makes it easier to slide the clay out when it is dry,” Molaroni says, showing the clean-cut sections of the mold. She closes the mold back up making sure every piece is secure before placing it back on the shelf, then walks out back towards the glazing station and then out into the main workshop.

Today there are only five people working for the shop. “Most of them usually only paint a couple hours in the morning and then a few hours at night,” Molaroni explains. “They are usually doing this as a hobby.”

Only one works at the shop, and her name is Gilberta Agabiti, and she has been working in the Molaroni store since she was a little girl.

“I have always had a talent for drawing,” says Agabiti while working on a Margherita design on a small, white, curved plate. “I started when I was 13 because I was rejected from my third year of middle school. So my father sent me here to work.” After a few years Agaibiti passed middle school and attended art school in Pesaro. It has now been 32 years that she has been working for the Molaroni family.

The process to make these beautiful pieces is done mostly by Molaroni herself. First she begins by using what she calls “creata” or clay. This material is also referred to as earth, making the ceramics seem even more connected to Pesaro. The clay is then pressed into the mother stamps or molds that were created in 1880. The stamps are made of a soft concrete like material and are piled floor to ceiling in the workshop behind the store front.

After about a day in the mold the clay is ready to be fired. The oven has to be set at 950 degrees Celsius, around 1700 degrees Fahrenheit, in order to get rid of any impurities that might have existed during molding. The ceramics cook for 12 hours and then are left to cool inside the kiln.

After the first firing the ceramics turn to the red color of terracotta. Molaroni then dips the pieces into the white glaze, which is what makes the pottery majolica.

The next step is where the rest of the workers come in. The white pieces are ready to be painted with the different motifs.

“I will take the pieces to the workers who work at home,” says Molaroni. Then I will pick them up.”

Agabiti and Molaroni work on the designs out in the shop using small turntables that allow them to rotate the pieces as they paint. Agabiti uses a brown paint that fades while the pieces are being cooked in order to center the design and keep the flowers and vines in the right place. Molaroni does everything freehand.

After a piece is done being painted, Molaroni will take it in the back to the crystallization room. She sprays the pieces with a then sheen of clear material to give the majolica its signature shine. She then places the items in the oven again to cook at a lower temperature.

“When it is done and there are no imperfections then it is ready,” Molaroni explains. “If there is something wrong, and that is usually how it goes, it has to be refined again and then cooked again and then it’s ready.” She shines a light into a kiln holding various pieces in process. Sitting on separate terracotta racks, some look—to the untrained eye, at least—as though they could be placed on the shelf for sale that day. Molaroni, however, points out small imperfections that would have to be fixed. A small plate has a clump of white paint. A bowl styled with the blue rose has a rim that reaches too far down.

On a recent afternoon in June, a customer walks into the store, admiring this commitment to perfection in every piece and detail. “You pay for the artistry” says Gianni Vitellone, a travel guide from Australia whose family is from Italy. “These pieces take experience, and the care that goes into them is clear to see.”

“We stick to the tradition and use specific steps in order to create the majolica,” says Molaroni later, closing the kiln and turning off the lights in the workshop. “If we don’t do this, then it isn’t tradition. And since we are the Molaroni family, we create majolica. It is what people know us for.”

Slideshow

This article also appears in Urbino Now magazine’s Arte e Cultura section. You can read all the magazine articles in print by ordering a copy from MagCloud.