Speleologists rediscover a network of aqueducts beneath Urbino’s busy piazzas

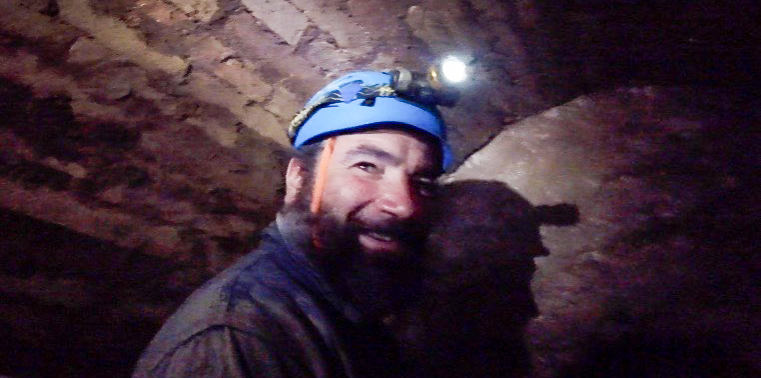

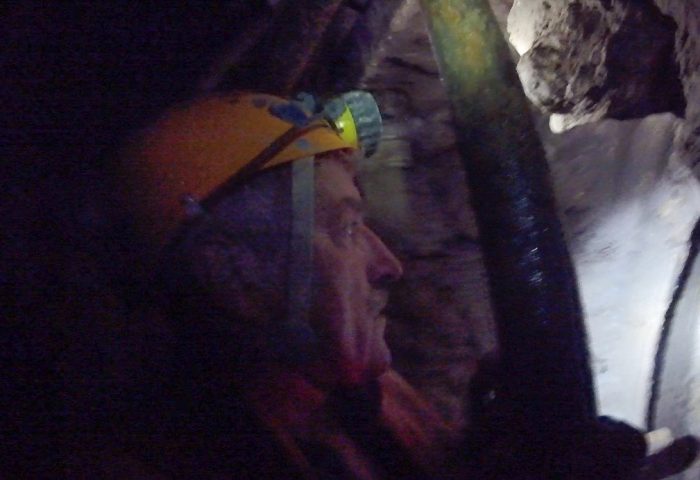

URBINO, ITALY – While thousands of tourists are walking through Piazza della Republica marveling at the historic Renaissance buildings this city is famed for, Filippo Venturini is also surrounded by history – but he’s 65 feet beneath them being guided through dark, narrow sandstone tunnels by the slender beam of his headlamp.

“It is a very rare kind of building for a Roman aqueduct,” said Venturini. “Very few people know about it.”

Venturini is part of a team of cave explorers who have been rediscovering a vast network of tunnels built as aqueducts by succeeding generations of Urbanite from Roman times through the 20th century.

The system dates back to aqueducts built by Rome during the first century A.D. to carry water to the city from a spring located at the top of a nearby hill, which today is the location of the 15th century Fortress Albornoz. It runs for 886 feet below the cobblestone streets to an area below the piazza.

Last used in the 1880s when a new, modern water transportation system was built to meet the needs of the growing city, it was gradually forgotten by succeeding generations. But in 1998 old documents found by a group of speleologists – cave researchers – led to its rediscovery.

Now the aqueduct is being brought back to life by the Group of Speleologists of Urbino (GSU), a club of about 30 professional and amateur researchers.

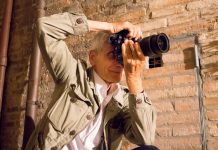

On a recent night Venturini, an archeologist, and Manlio Magnoni, one of the original founders of GSU, gave a tour of the aqueduct.

Access to the aqueduct is inside a small art theatre building near the top of the city’s highest hill.

“I hope you are scared,” Venturini joked as he opened the doors of the theatre building and stepped inside. A short walk later he entered into a small white room, pulled a square of tile up from the floor revealing a massive hole in the ground – the entrance to the maze of aqueducts.

The Roman aqueduct – named the Santa Lucia Aqueduct – runs about 800 feet beneath the ground from the theatre building all the way down to Piazza della Republica. It varies from three to 18 feet in width.

“It was more then one century since anyone had been in the aqueduct when they found it,” said Venturini. “It was filled with mud.”

He explained that the GSU cleaned the aqueduct by taking pressure washers to first scour a path through the mud. And now it carries water again.

On this night Venturini and Magnoni wore special jumpsuits, gloves, boots, and helmets with headlamps before entering the aqueduct.

“A special suit is made for going inside the aqueduct,” said Michele Magnoni, a web designer, and Manlio’s son. “Usually we wear two suits, one to keep our body warm which is internal and an external layer that keeps the water out. The only way to enter the water part of the aqueduct is to have a scuba suit that keeps the water out.”

The small holes on the side of the walls were used to hold candles so that the roman workers could see.

One by one the men carefully stepped down the entrance eventually finding the bottom about 60 feet below the surface of the city. The dark was broken only by the tight beams of their headlamps. As they began sloshing forward through a mixture of shallow water and mud, Venturini stopped and pointed out a brick on the bottom. “This was a roman roof tile used to build the aqueduct,” he said. “The small holes on the side of the walls were used to hold candles so that the roman workers could see.”

About 230 feet later the path ended at a brick-walled tunnel filled with clear, shimmering water – they had arrived at the water supply that would continue to run about 656 more feet.

Venturini said many aqueducts were built over the years to meet the water demands of the growing city. The water is still clean but the town does not use it anymore, he said. Instead it is connected to the sewer.

“This aqueduct is the biggest that the group has found,” he said. “Now the group is trying to preserve it.”

The fountain dates back to the Romans but was restored and used over the centuries that followed.

The only way for the speleologists to continue through the water-filled path was with scuba gear but neither of the men had brought it, so they turned back.

But they were not finished exploring in the dark.

On the way back they turned into a new tunnel smaller than the rest of the aqueduct. It looked almost impossible to walk through, but Venturini got down on his hands and knees and slithered through the narrower space soaking his jumpsuit with mud and water.

He stopped about 15 minutes later when the path came to an end and again history surrounded him. He pointed out two pathways he said date back to the Roman period.

“We were digging to find the rest of the aqueduct (and) we have found two new channels and maybe one more,” he said.

These pathways have remained untouched since the Romans. The two tunnels were exactly how the Romans built them and unique since they give an exact tie back to the Romans.

Venturini said the GSU will continue to study the Santa Lucia aqueduct in hopes that it leads to more ancient history. GSU’s goal is to bring light to the underground world, even as modern-day tourists continue to walk in the sunlight 60 feet above them.