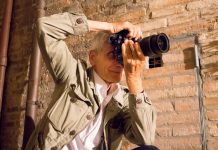

Giovanni Maestrini protects the inhabitants of the Church of the Dead

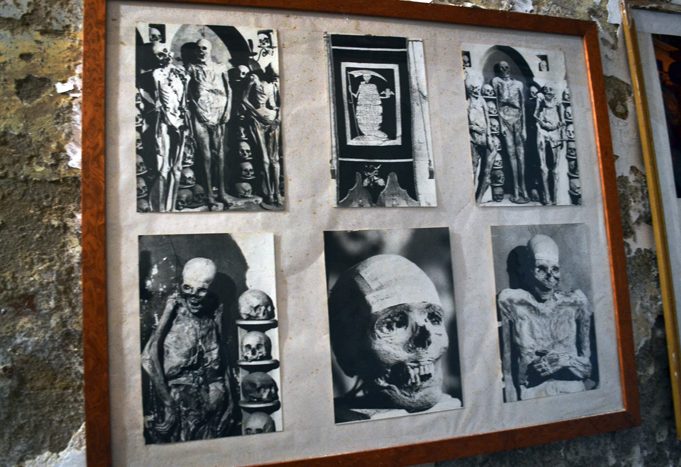

Eighteen pairs of mummified eye sockets stare through the glass enclosures. The bodies, fragile and red, are perfectly preserved—every bone distinct, every cause of death evident. They stand as though still alive. Above the glass cases, 100 skulls lie in piles. A lamp of human bones hangs solemnly in the center of the display, illuminating the array of faces. An eerie presence reverberates in the Chiesa dei Morti, also known as the “Church of the Dead.”

But 34-year-old Giovanni Maestrini, caretaker and tour guide at the church for seventeen years now, is not fazed. “I am very happy here. It is not dangerous and the dead do not bother me,” says Maestrini. His personality brings a lively presence back to the church. His face wears a permanent smile peeking through a clean-cut beard, and his deep voice echoes loudly throughout the structure. His charismatic persona and his passion for history make the Chiesa dei Morti an attraction to experience in Urbania, Italy.

* * * * *

The Chiesa dei Morti is the oldest church left standing in Urbania. Initially finished in 1380, it is tucked in an alleyway just a two-minute walk from the town’s center square. The exterior is washed-out stone and brick. The white archway is elaborately carved, an intricate cross attached on top. Opaque glass intertwines into the worn, wooden door. Inside, faux-marble columns guard either side of the altar, extending to the ceiling. A painting of St. John the Baptist from the year 1500 by Giustino Episcopi, a local artist and student of the famous Giotto, is mounted above the altar between the columns.

Until 1983, the church essentially served as a funeral home, operated by the Confraternita della Buona Morti, or the “Confraternity of Good Death.” This organization helped the sick, and buried and documented the dead of Urbania.

“I am very happy here. It is not dangerous and the dead do not bother me,” says Giovanni Maestrini.

The confraternity discovered the mummified bodies in 1833 when Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the removal all buried bodies from the city for health reasons. When digging up the bodies, 17 of them resurfaced completely preserved due to a special mold in the soil, currently unidentified, that naturally sucked the fluids from the bodies and left them intact. The mummies maintain a red hue from the clay in which they were buried. Although from the same cemetery, the 100 skulls displayed did not undergo the natural mummification process because the mold grows only in certain areas. This bizarre phenomenon appears only in two other places in Italy, near the towns of Ferentillo and Venzone.

At the age of 14, Maestrini first started doing tours at the Chiesa dei Morti. “I first met the old caretaker of this building [Giuseppe Duci] when I was doing my training with the town hall,” he says. Through this high school internship, Duci took a liking to Maestrini as his successor. “In my opinion, Giuseppe saw his youth in mine,” says Maestrini.

They worked together for fourteen years. Not only did Giuseppe Duci teach Maestrini about the history of the church, but he also taught Maestrini how to interact with the people. “He was a charismatic person,” says Maestrini. Duci passed away just two years ago.

* * * * *

To the left of the altar, a little door opens into the second part of the church. Maestrini walks through the door, then enters a stone archway on the right.

Glass enclosures curve like a crescent moon around the room; the mummies inside stare in every direction. On the wall above the glass cases, a deteriorating fresco depicts St. Francis. A large white cross is tiled into the black floor. Maestrini instantly begins speaking.

The glass enclosures were built in 1983, he says, for preservation purposes—to prevent tourists from touching the bodies. The ten glass casings hold one or two bodies each, and above each case is a quote from the Bible in Latin. Each mummy stands distorted.

Each has its own story; Maestrini only explains a few. One woman died from a C-section, and the woman next to her suffered from hip dysplasia, which, at the time, was impossible to operate on. Another woman suffered from rickets, or malnutrition of vitamin D and protein. The most disturbing story is that of a man who was buried alive, says Maestrini. He had catalepsy, when the heart beats slowly and the body temperature drops, mimicking death. The goosebumps on the man’s skin are still preserved.

The last story Maestrini tells is that of Vincenzo Piccini, a prior of the Confraternity of Good Death. He stands in the center of the crescent, wearing the clothes of the confraternity, the clothes he was buried in. After discovering the mummies, Piccini studied them for a year, inventing a chemical that would preserve his body as well. He died in 1834.

“My favorite part of this job is when I am with the tourists explaining the history,” says Maestrini. His face gets brighter and brighter the longer he speaks. His voice gets louder and louder as he goes more in depth.

* * * * *

When Maestrini first started working at the church, it looked much different than it does now. The Confraternity of Good Death was disbanded in 1983, but the church’s caretakers, like Duci and Maestrini, continue to preserve and restore the church and its contents. The entrance of the building was recently cleaned, and a few years ago the roof was repaired for 30 thousand euro. The 2 euro per visitor that Maestrini collects will someday pay to restore the fresco of St. Francis in the display room.

“I absolutely feel like I am a member of a confraternity because of my role in preserving this church. I am a future member,” he says, laughing. “I feel like I have a responsibility to keep this preserved for the future.”

“It takes a special person to work here,” says Giuseppe Maestrini.

According to the town’s tourist center, the Chiesa dei Morti is now the most popular attraction in Urbania, bringing on average 12,000 visitors per year since 2000. People from all over the world come to visit: European tourists, as well as Americans, Australians, and tourists from Africa. The Chiesa dei Morti has gained a lot of media attraction as well, from National Geographic to local TV stations.

* * * * *

Maestrini’s feelings about his job at the Chiesa dei Morti have never changed; they are always intact, always the same. “I like being with the people because here it’s a place where you never see the same people; you always see somebody different and that’s what I really like about it.”

A few years ago, Maestrini’s father, Giuseppe, started helping in the church whenever Maestrini was sick; Giuseppe has been helping sporadically ever since. To both father and son, it is important to be respectful while working in the church—it reflects on the reputation of the whole town. “The reviews later are always better,” says Giuseppe, “so you give the whole town a more respectable image, people come back here.”

“It takes a special person to work here,” says Giuseppe.

Though still young, Maestrini is starting to think about a successor, who must be carefully chosen. “When I will be old, I would like as well to leave this place in good hands,” says Maestrini.

His laugh thunders through the small church.

Slideshow

This article also appears in Urbino Now magazine’s La Gente section. You can read all the magazine articles in print by ordering a copy from MagCloud.